Our written language is partially based on sounds. Many of the first words students read have a predictable connection between the letters and sounds (i.e. cat, dig, mop). However, students quickly run into words that do not seem to follow the letter-sound associations they’ve learned. Consider the common early sight words does, two, and says. If the spelling of these words simply matched their sounds and common orthographic patterns, we might write duzz, too, and sezz. Students often end up memorizing these types of words individually, making English seem less and less reasonable one sight word at a time.

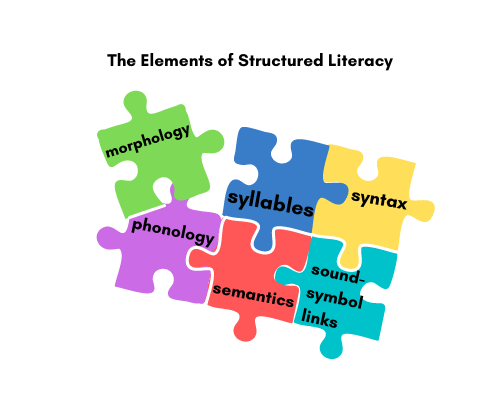

If students only learn about sound-related patterns, English seems much more mysterious than it actually is because our written language actually reflects both sound and meaning. The meaning of a word impacts the way it is written as much (or more!) than the sound. This means that teaching meaning-related patterns (morphology) should be a central piece of literacy instruction. You can see this reflected in the elements of Structured Literacy.

One way to improve understanding of morphology is through word inquiry. When trying to understand the spelling of a word, we can ask questions and use multiple resources to test our hypotheses. Structured Word Inquiry pioneer Pete Bowers suggests these questions to guide students’ word studies:

- What is the sense and meaning of the word?

- How is it constructed?

- What related words can you find?

- How are the graphemes functioning in your word?

These types of questions lead to the discovery that does comes from do + es and says comes from say + s. The word two comes from a Proto-Indo-European root dwo-, which also produced words like twin, twice, and twelve. The pronunciation of morphemes (meaningful word parts) often shifts across words, but their meaning remains consistent.

Does your child feel like English is illogical and frustrating? Sign up for Structured Literacy intervention today, and we can help clear up their confusion.

2 thoughts on “More than Sounds”